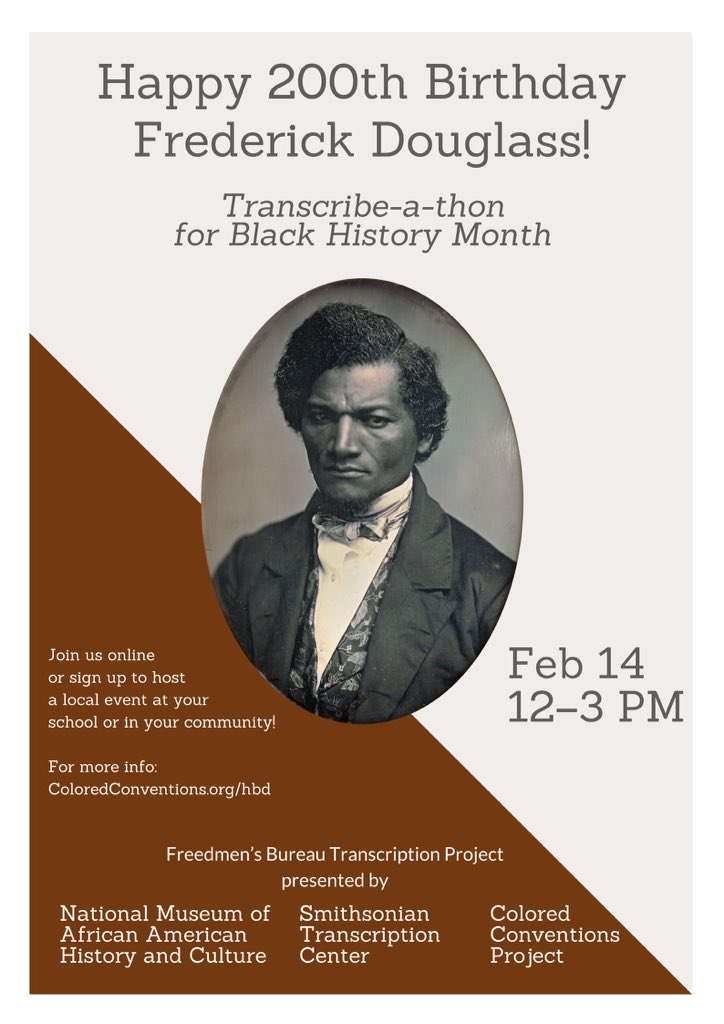

Celebrating Frederick Douglass' Bicentennial through Transcription

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) was a social reformer and advocate, abolitionist, orator, writer, minister, and statesman. Born to an enslaved family in 1818, Frederick Douglass never knew his actual birthday, a fact not uncommon for those enslaved. So, after escaping slavery in 1838, he chose his own date: February 14. This year marks the 200th birthday of Douglass, and we're celebrating his bicentennial all year long.

In his lifetime, Douglass published multiple autobiographies, edited four different abolitionist newspapers, traveled the world speaking out against slavery and in the pursuit of social justice, and helped move forward legislation regarding suffrage for African Americans and women. One of the greatest reformers in United States history, Douglass profoundly influenced the social and political history of the nineteenth century, and continues to influence and inform us today.

On February 14 of this year, we honored Douglass's birthday by partnering with the Colored Conventions Project to co-host a multi-city transcribe-a-thon for the Freedmen's Bureau records, part of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture and the National Archives. The event, which was livestreamed and connected via social media, featured representatives from the Smithsonian as well as a dramatic reenactment of Douglass' speech at the 1883 national Colored Convention in Louisville, Kentucky. We were blown away by the response, with over 750 pages transcribed, 402 pages reviewed and approved, and 600 new registered volunpeers.

But there's still so much left to discover and transcribe! Please join us in continuing our year-long celebration of Douglass as we explore, transcribe, and review more projects from around the Smithsonian related to African-American history, abolition, and Douglass's important work and legacy.

What Frederick Douglass-related materials are available in the Transcription Center?

A number of collections related to Frederick Douglass are held in the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum (ACM). ACM was founded in 1967 as a place to present the stories and experiences of urban residents and connect with the local African American community. As a resident of the Anacostia neighborhood from 1877 until his death in 1895, Frederick Douglass looms large in the history of Washington, DC. He is well represented in ACM’s collections and has been the subject of several exhibitions curated by the museum, including “The Sage of Anacostia” (1969), “The Frederick Douglass Years” (1970, traveling), and “The Anacostia Story: 1608-1930” (1977).

Image: Frederick Douglass National Historic Site and Home, Washington, DC. National Park Service.

Current and completed ACM transcription projects related to Frederick Douglass highlight this history:

Douglass' Monthly (1858-1863) Editions: September 1860, Vol. III - June 1863, Vol. V

This was one of four papers published by Frederick Douglass, and like his others, was dedicated to abolitionism and social reform. News of political, social, and racial tensions were featured, as the nation's sectional divisions grew, and Civil War broke out, and stories of emancipation, slave insurrection, and African American soldiers were highlighted prominently. Issues of this newspaper were made available for transcription through the Smithsonian's Anacostia Community Museum Archives, and were enriched and made more accessible by our digital volunpeers.

Address by Frederick Douglass Delivered in the Congregational Church on the Twenty-First Anniversary of Emancipation in the District of Columbia

On April 16, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed into law the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act. The act freed approximately 3,000 slaves and paid slave owners for their release, thus ending slavery in the District of Columbia. Twenty-one years later, on the anniversary of emancipation in D.C., Frederick Douglass delivered a speech at Congregational Church. This pamphlet includes the address delivered by Douglass, along with correspondence between Douglass and others.

Oration by Frederick Douglass Delivered on the Occasion of the Unveiling of the Freedmen's Monument, April 14, 1876

Accompanied by President Ulysses S. Grant and other officials of the federal government, Frederick Douglass delivered a speech at the dedication of the Emancipation Memorial in Lincoln Park, Washington, DC on April 14, 1876. Designed and sculpted by Thomas Ball, the monument depicts Abraham Lincoln holding the Emancipation Proclamation and holding out his right hand over a kneeling ex-slave. The statue was funded mostly by formerly enslaved persons and is also known as the Freedmen's Monument.

Many other collections related to Frederick Douglass are held in the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). Along with various images and prints of - and related- to Douglass, the NMAAHC has collected a number of archival materials and museum objects created by or about Douglass as a part of their mission to promote and highlight the contributions of African Americans

Explore recently launched Douglass Transcription Projects from NMAAHC below, and help us transcribe these materials to increase their accessibility and enrich our understanding of Douglass's immense impact on American history:

Letter Written by John Brown and Frederick Douglass to Brown's Wife and Children

A letter written by John Brown and Frederick Douglass from Rochester, New York, on January 30, 1858, to Brown's wife and children. The letter is handwritten in black ink on the front and back sides of a single sheet of paper. The letter is first written by Brown, who does not sign his portion beyond "Your Affectionate Husband and Father." Brown writes of missing his wife and children very much, but of not being able to visit them. He also asks his daughter Ruth about her husband, Henry Thompson, becoming involved in Brown's "school," coded language for Brown's militant abolitionist dealings. He further speaks of recruiting his sons for his work and requests that the family write to him under the name "N. Hawkins: Care of Fred'k Douglas [sic] Esq'r Rochester N[.] Y." Douglass writes on the lower half of the verso page with his words oriented three different directions to fit the page. He speaks of his friendship with the Brown family and invites any of them to his home, where John Brown is staying, signing as "Fred. Douglass."

Frederick Douglass' Paper, July 28, 1854

The July 28, 1854 issue of Frederick Douglass' Paper, a Rochester-based weekly newspaper published and edited by Frederick Douglass that centered on antislavery efforts and other social reform causes. The title [Frederick Douglass' Paper] is printed in large text across the top, just underneath the title are the issue details printed between two horizontal black lines: [Vol. VII, No. 32, ROCHESTER, N.Y. FRIDAY JULY 28, 1854., Whole Number 344]. The text of the paper is densely concentrated in seven vertical columns and there is both a vertical and horizontal crease through the center. An inscription of the name [Stephen Reeves] is written in black ink at the top right corner of the front page. The last page contains a large advertisement: "Call for a National Emigration Convention of Colored Men to be held in Cleveland Ohio" and is signed in print by Martin R. Delany.

Broadside for "Men of Color" Recruitment

In June 1863, the Union Army authorized the recruitment of African Americans to fight in the Civil War. Citizens of Philadelphia held a convention to promote enlistment. Luminaries of abolition including Anna E. Dickenson and W.D. Kelley joined the great orator Frederick Douglass at the convention. Douglass joined fifty-three local leaders in signing this call-to-arms. African Americans ratified the over sized document to endorse enrollment.

The North Star, Vol. 1, No. 37

The North Star, later called Frederick Douglass’ Paper, was an antislavery newspaper published by Frederick Douglass. First published on December 3, 1847, using funds Douglass earned during a speaking tour in Great Britain and Ireland, The North Star soon developed into one of the most influential African American antislavery publications of the pre-Civil War era. The name of the newspaper paid homage to the fact that escaping slaves used the North Star in the night sky to guide them to freedom. The paper was published in Rochester, New York, a city known for its opposition to slavery. The motto of the newspaper was, “Right is of no sex—Truth is of no color—God is the Father of us all, and we are brethren.” Published weekly, The North Star was four pages long and sold by subscription at a cost of $2.00 per year to more than 4,000 readers in the United States, Europe, and the West Indies. The first of its four pages focused on current events having to do with abolitionist issues; pages two and three included editorials, letters from readers, articles, poetry, and book reviews; the fourth page was devoted to advertisements. In the paper, Douglass wrote with great feeling about what he saw as the huge gap between what Americans claimed to be their Christian beliefs and the prejudice and discrimination he witnessed.

This issue, published September 8, 1848, contains several anti-slavery essays and letters, including a letter from Douglass to his previous enslaver Thomas Auld, titled [To My Old Master], as well as a critique of the Liberian colonization movement, news of the rebellion in Ireland, poetry, notices of anti-slavery society meetings around the region, and general advertisements.

Handbill for a Performance by the Fisk Jubilee Singers

The Fisk Jubilee Singers were an African American a capella ensemble established at Fisk University in 1871, known for singing spirituals. In 2002, the Library of Congress honored their 1909 recording of "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" by adding it in the United States National Recording Registry. The song on this handbill was written by Frederick Douglass while he was enslaved. The other side of the handbill has a letter from Samuel Clemens, better known as Mark Twain, about how much he enjoyed the Singers’ performances. Help us transcribe this handbill and learn more about music’s importance in America’s history.